ESG Accounting Challenges in Mining & Resources

Introduction to Certified ESG Mining Accounting Course

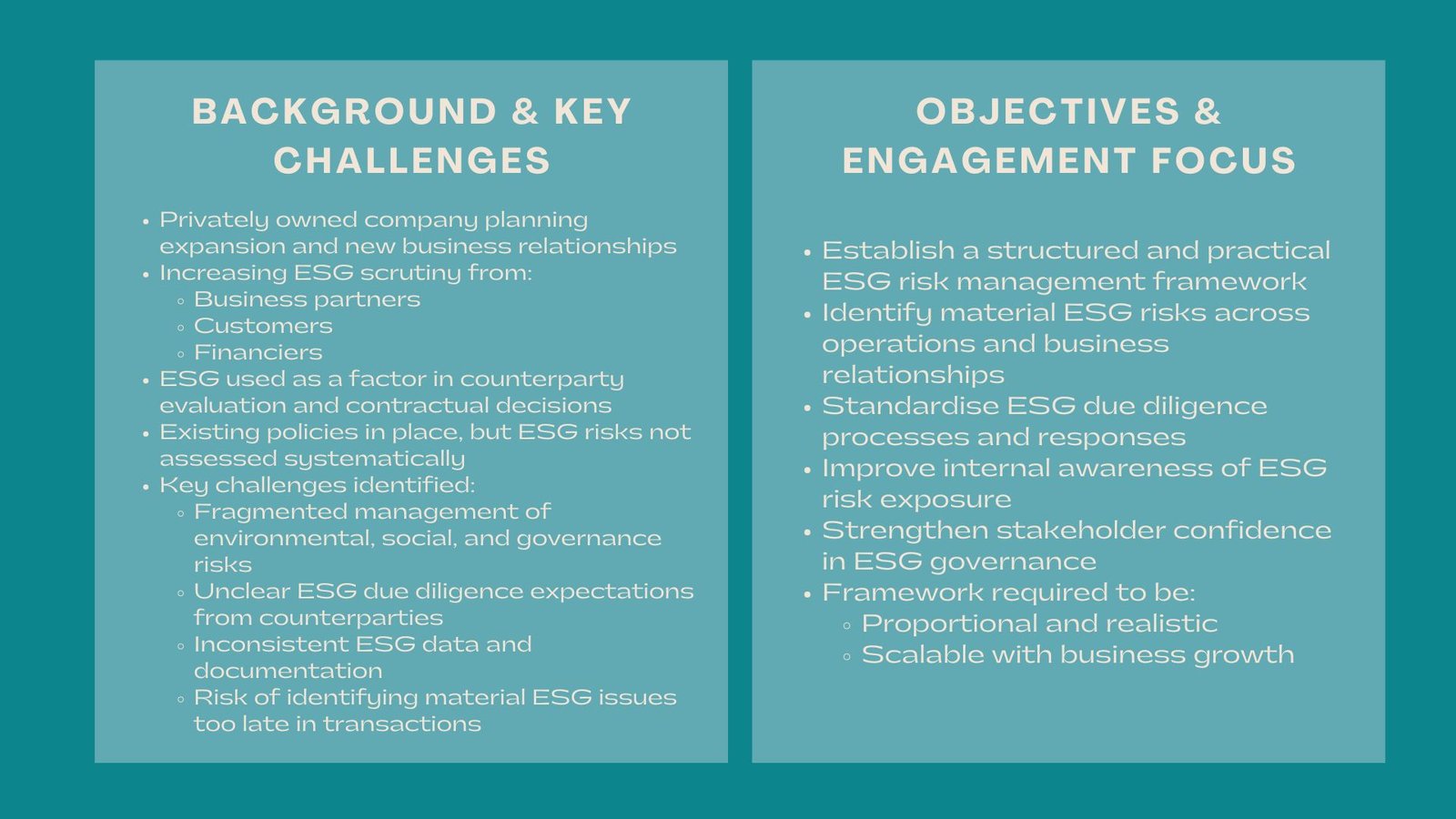

The mining and resources sector is being remodeled by the environmental, social and governance (ESG) expectations to ensure that investors, regulators and communities seek more visible accountability on the effects of sustainability. The mining business is sensitive ecologically, it deals with the extraction of significant resources, and the mining firms are usually highly scrutinized regarding land use, emission, safety and community relations. With the development of global standards and the increase in disclosure requirements, the capacity to develop precise, defendable, and decision-supportive ESG accounting has turned out to be the focus of corporate disclosure and the sustainability of businesses in the long term.

In this article, the author will examine the unusual accounting pressures that mining businesses undergo to the extent of measuring environmental performance, reporting of social effects and showing governance integrity in a manner that fulfills global expectations and enables the business to have a sustainable business strategy.

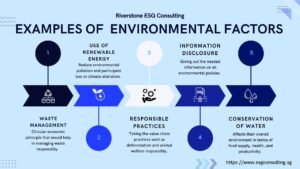

1. Complex Mining Environmentally Accounting.

1.1 The Measurement of Multi-Layered Operations Emissions.

One of the most complicated ESG accounting activities is the measurement of emissions because mining is an energy-consuming process. The companies should take indirect emissions into consideration that are represented by the use of diesel-driven equipment, blasting, and the generation of electricity on the spot, but they must also take into consideration direct emissions of using ore transportation, processing plants, and the final refining.

Emission baselines in the production of Cd are complicated by factors like variable ore grades, varying levels of production and various extraction processes. The challenge faced by many operators is to have uniform methodologies at different sites especially where the operations in the past did not include the use of digital monitoring systems. The adoption of recognized frameworks, including Mining ESG accounting standards, has become essential for ensuring comparability and auditability.

1.2 Rehabilitation Provisions and Long-Term Environmental Liabilities

Liabilities of mine closure and rehabilitation of the land probably present a lot of complications in the financial and sustainability reporting. The future restoration cost must be estimated taking into account the changing regulations and climate risk, the effect on biodiversity and the long term of the water treatment requirements.

As one such instance, in Australia and Canada, large-scale miners have been under regulatory scrutiny to make more rehabilitation provision following independent audits of understated environmental liabilities. The accounting teams are required now to model the costs decades later, to use the uncertainty adjustments, and to align the disclosures with the requirements of the IFRS, sustainability standards, and government expectations.

1.3 Water Reporting and Water Management Variability.

Water is also among the most important environmental limitations to mining firms particularly in areas that are characterized by a lack of water. Proper accounting of water abstraction, usage, recycling levels, and the quality of discharge requires powerful monitoring facilities.

When mines are dependent on more than one water source, groundwater or surface water, and third party suppliers, then it becomes difficult to have several reporting streams. The difference between operational monitoring and ESG reporting is frequent and gives rise to the investors questions regarding the accuracy and transparency.

2. Miners face financial difficulties through social accounting.

2.1 Measuring Community Impact and Local Development.

The social impact is often sensitive and complicated as mining activities are often overlapping with both local and Indigenous communities. The companies have to measure the local employment, supplier development schemes, land access payments and community investment schemes.

The challenge is on how to translate the qualitative community engagement into standard measures that are compatible with international disclosure standards. As an example, the levels of community satisfaction or conservation of cultural heritage are not easily measured using traditional accounting instruments but their absence in the ESG reports undermines credibility.

2.2 Safety Reporting of the Workforce in High-Risk Workplaces.

In mining, safety performance is an essential part of ESG because the industry is rather risky. Although lost-time injury frequency rates (LTIFR) and fatality rates are both typical measures, their inconsistency in definition and variability in reporting limits often make it challenging to compare them.

Practical examples of this challenge can be identified: multiple mining enterprises working in Africa, South America, and Asia have complained that it is difficult to standardize safety measures because some contractors provide substandard reporting, and there are no uniform standards of reporting safety metrics across all countries, as well as because of the difference in legal standards and the lack of a single set of international standards in the area of the standardization of safety metrics.

2.3 Human Rights and Labour Reporting Requirement Management.

Mining ESG assessment is based on human rights, such as the working conditions, security practices, and displacement of communities. However, to consider human rights performance, it is necessary to bring legal adherence, grievance, and audit findings into a systematic reporting system.

The companies also tend to have difficulties recording the supply-chain labour practices, particularly in the case of raw materials being produced in the artisanal mine area where regulation is minimal. This creates a level of uncertainty on disclosures and an increased risk of reputational harm in the event reported data is not complete and inconsistent.

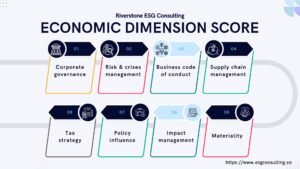

3. Expectancies of Governance Accounting and Transparency.

3.1 The company will also establish anti-corruption controls and disclosure requirements to prevent corruption in the country of entry.

There are numerous mining companies in jurisdictions of weak, moderate, and high regulatory enforcement that exposes them to more bribery, facilitation payments, and political risks. The accounting of governance should reflect on anti-corruption training, reporting of incidents, third-party due diligence, and resolving of cases through whistleblowers.

Nonetheless, lack of consistency in the systems of data collection in the subsidiaries leads to gaps in reporting. Shareholders are becoming more agnostic that mining companies should present elaborate governance reports that show effectiveness of oversight and management of ethical risks.

3.2 ESG Risk Integration and Board Oversight.

Board of directors can be looked to as playing a major role in the assessment of environmental liabilities, risks of community and operational safety. However, several mining boards do not have standardized ESG risk dashboards or integrated reporting systems to monitor the sustainability metrics in relation to the financial performance.

This tends to lead to the discontinuous revelation of governance in which ESG narrative is inconsistent with performance information. External ratings on transparency and accountability are more likely to favor companies that incorporate ESG risk in enterprise risk management (ERM) and reporting their activities to the board.

3.3 Essays on Third-Party Assurance and Audit Challenges.

There is an increasing trend towards third-party verification of ESG information in the mining industry, as a result of increased investor expectations. There is often a discrepancy between operational systems and reported sustainability metrics, which are often emphasized by the assurance providers e.g. emissions factors or water usage data.

External assurance unveils internal control loopholes, and this forces the mining firms to restructure their data management procedures and embrace digital monitoring technologies. As the ESG compliance mining sector evolves, independent verification is becoming a determining factor in investor confidence and regulatory acceptance.

4. Strengthening ESG Accounting Capabilities in Mining

4.1 Digital Monitoring and Real-Time Data Systems

The use of IoT sensors, automated emission records, and built-in reporting tools to modernize data collection will go a long way to improve the accuracy of ESG accounting. Digital monitoring by mining firms has shown to provide a better quality of disclosure and less assurance issues.

4.2 Matching Operations to Global Standards.

Compatibility of ESG accounting with the global accounting of the international accounting standards like the IFRS S2, GRI Mining Sector Standard and ICMM guidelines improves comparability and investor confidence. Major businesses have also started to map operational metrics to these frameworks so that they simplify reporting.

4.3 Cross-Functional Capacity Building.

The cross-functional collaboration of the finance department, sustainability department, operations department, and legal department is necessary to achieve effective ESG accounting. Numerous mining companies invest in special training courses to develop internal knowledge in the field of ESG measurements and scenario analysis.

Conclusion

The mining and resources industry has one of the most complicated ESG accounting issues of any sector owing to the magnitude of their environmental impact, the intensity of their dealings with the community, and the level of governance pressure. To resolve these issues, the data systems should be stronger, and cross-functional skills, a better representation of the global standards, and transparent reporting should be considered. With greater regulatory oversight and pressure on companies to be more consistent in disclosure of ESG-related matters, companies that reinforce their accounting systems will be in a better position to manage risks, attract investment, and enable a more responsible future of the industry.