ESG Reporting in the Construction Industry: Strengthening Compliance Through Integrated Data and Risk Management

Introduction to Certified ESG Construction Reporting Training

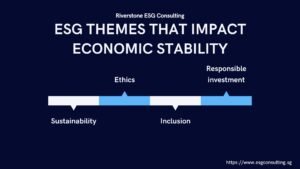

The construction sector is quickly evolving as the regulators, investors, clients, and communities are seeking more environmental responsibility and safety performance as well as governance transparency. Construction activities are also characterized by high degrees of environmental effects, resource use and operational risk unlike most other sectors. Consequently, ESG reporting has emerged as an essential need to builders, contractors and infrastructure developers who want to remain competitive, deliver expectations of regulators, and obtain long term financing of projects.

This paper focuses on just one of such areas: the ability of the construction companies to develop a strict, data-intensive ESG reporting system and achieve a better level of compliance, mitigation of project risks, and gain stakeholder trust. The discussion includes reporting structures, alignment of operations, and real-life examples in the industry that show why transparency is vital in the construction-related ESG performance.

1. The reason why ESG Reporting is important to the construction sector.

1.1 Increasing Regulatory and Stakeholder pressures

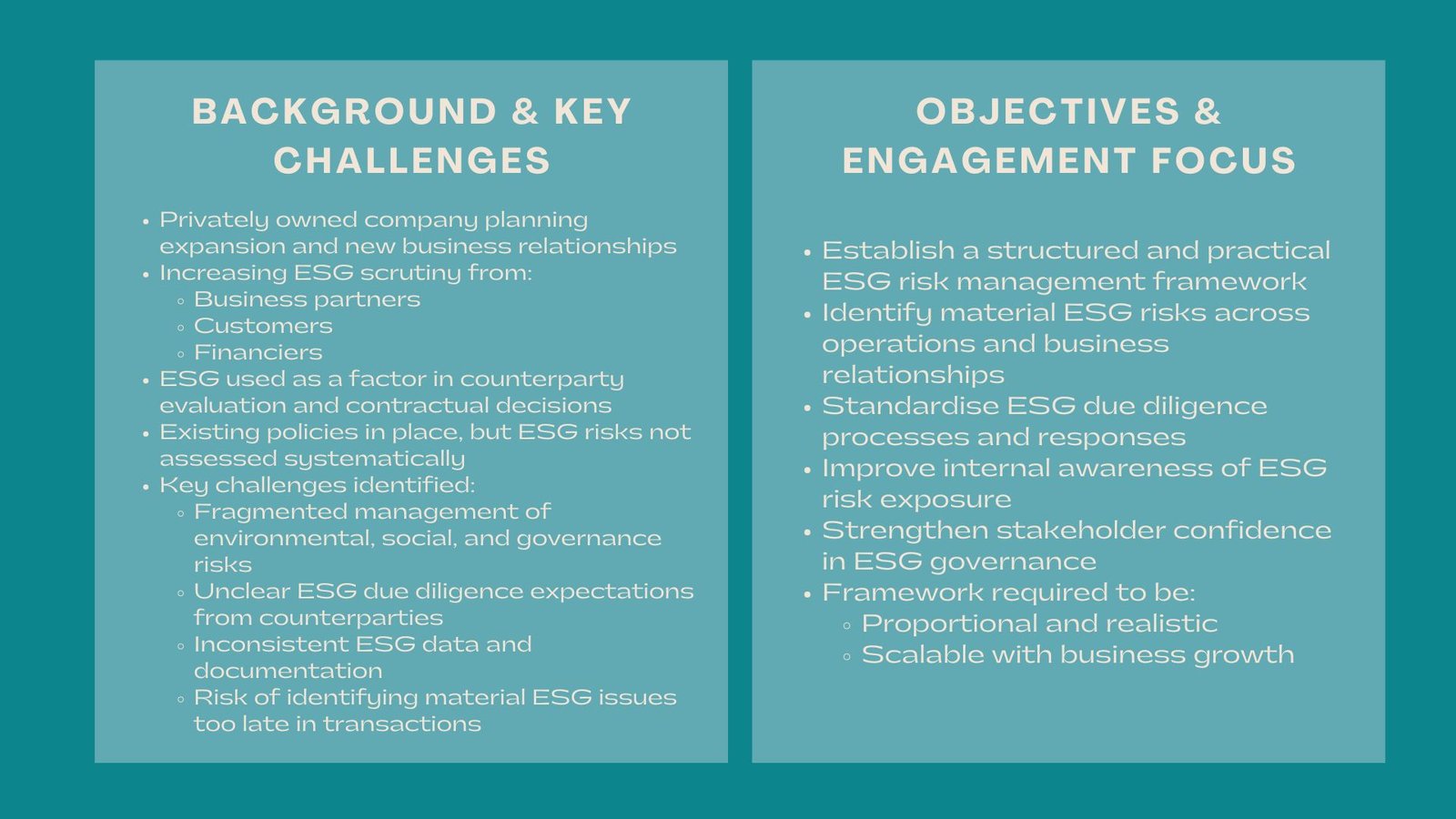

The construction industry is experiencing increased demands of sustainability reporting in the areas of environmental protection, occupational safety, community impact and governance control. Governments are putting stricter regulations on emissions, waste disposal, water use and labor practices. Meanwhile, institutional investors are more inclined to consider only those contractors who are able to show strong ESG indicators and have established sustainability roadmaps.

Large property developers, such as, now screen contractors on their sustainability credentials, which demand project level disclosure (carbon projection, health-and-safety reporting and waste-to-landfill results). Such requirements are forcing the construction companies to implement well-organized reporting mechanisms to prevent bid loss.

1.2 Increasing Demand by the Project Owners and Lenders.

Infrastructure projects of large scale that are financed by banks, sovereign wealth and development agencies are required to adhere to stringent ESG provisions. Third-party environmental assessment, social impact analysis and contractor government control are frequently mandatory in loan agreements. Living up to these expectations may result in a slow project approvals or access to capital.

As such, many companies are adopting Construction ESG compliance guidelines to standardize internal practices and efficiently meet reporting expectations across multiple stakeholders.

2. Building a Robust ESG Reporting Framework

2.1 Establishing a Centralized Data Architecture

Construction projects result in huge amounts of data within the safety, environment, labor, procurement and operations processes. Nevertheless, the majority of companies keep this data in separate systems or in spreadsheet programs. An effective ESG framework must have a centralized data warehouse with real-time site performance, compliance and performance indicators.

Project management, environmental monitoring, and workforce analytics are increasingly automated by software platforms that are used to capture data. To illustrate, one of the key contractors in Australia adopted a digital compliance system where the dust-monitoring information, worker qualifications, and waste movement records are logged at all locations. This allowed improved ESG reporting and minimized time spent on the preparation of the audit.

2.2 Construction Activity Material ESG Issues Definition.

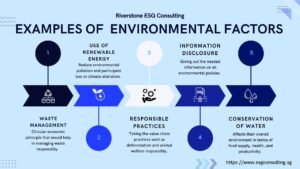

Construction firms should find out the most topical issues of their business, the exposure of risks, and the expectations of the stakeholders. These typically include:

- carbon emissions and material embodied carbon,

- wastes and pollution control,

- subsistence protection around the project sites,

- health, welfare and safety of workers,

- labor standards in supply chain,

- ethical subcontracting and transparency of purchases,

- community relations, noise abatement and land-use effects.

By addressing material concerns, the companies will be able to generate reports that will be insightful without the need to collect data that is not necessary.

3. Green Reporting: Waste, Carbon and Resource efficiency.

3.1 Value Chain management of Carbon emissions.

One of the most significant contributors to the global emissions is construction because of the energy-intensive construction, the use of heavy machinery, and the high carbon sources in the form of cement and steel. ESG reporting models stipulate that companies have to measure Scope 1, Scope 2, and in many cases, Scope 3 emissions.

One of the largest infrastructure developers in Japan has started to report embodied carbon on its large projects and employs low-carbon alternatives of concrete to lower its emissions by 30 percent. It is able to differentiate itself through the project bid due to the transparent reporting.

3.2 Waste, Water and Pollution Control Reporting.

The amount of waste and its improper disposal is still a risky area. Increased jurisdictions now mandate the in-depth monitoring of waste segregation, recycling, and the process of handling hazardous materials.

On highways and tunneling projects that are large, say, contractors have to provide monthly environmental reports, which include water-quality monitoring data, records of soil-movement, and air-emission levels. Formal reporting system can ensure that companies escape fines and litigation by the communities.

3.3 Sustainability in Material Procurement.

Construction firms are also becoming very vocal on their adoption of certified sustainable materials. The ESG indicators have become timber suppliers certified under FSC or PEFC, low-VOC paints, and recycled steel.

Open material sourcing also enables a company to deal with supply-chain risks and improve the requirements of green-building certification.

4. Social Reporting Workforce Safety, Labor rights, and Community impact.

4.1 Occupational Health and Safety as one of the Core Metrics.

One of the social measures that are subject to the most scrutiny in construction ESG reports is safety performance. Such indicators as Total Recordable Incidence rate (TRIR) and Missed-Time Injury Frequency rate (LTIFR) directly affect the choice of contractors and insurance claims.

A multinational engineering company has recently cut its LTIFR by 40 per cent using digital safety dashboards and APPs of real-time incidents reporting as well as compulsory training of contractors. These enhancements reinforced its ESG reports and competitiveness.

4.2 Ethical Labor and Supply-Chain Governance.

The supply chains in the construction sector have numerous subcontractors, which increases the threats of labor violations, undocumented labor, and uneven payment systems. The ESG reporting schemes have to reveal the labor audits, labor-welfare schemes, and ethical sourcing policy.

To illustrate, one of the Southeast Asian contractors has put in place biometric attendance measures and living wage policies on subcontracted employees. These practices are currently captured in its sustainability report and have increased the level of trust among foreign investors.

4.3 The Community Relations and Social License to Operate

The impacts of major projects on the local communities include noise, alteration in traffic, restriction of land access, and job creation. The frameworks of ESG systems compel firms to report engagement strategies, systems of grievance handling and the results of community investments.

An example of European developers of a rail uses public dashboards that demonstrate construction plans, noise levels and resolution of complaints. The strategy minimizes conflicts as well as promoting community acceptance.

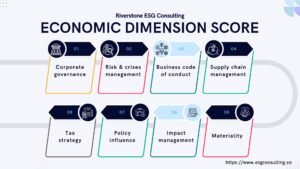

5. Governance Reporting: Risk Management and Control Compliances.

5.1 Anti-Corruption and Procurement Integrity.

The construction industry is a risky sector to bribery, tender abuse and procurement disputes. Good governance reporting is a sign that the companies have instituted ethical practices, and are audited of their practices independently, and that they have transparent subcontractor selection procedures.

One of the Middle Eastern construction groups also enhanced its governance disclosure by implementing digital tendering systems that minimize risks of corruption by automating approval processes.

5.2 Project Risk and Management and Board Oversight.

The reporting of ESG is increasingly demanding a reporting on how the board is involved in the sustainability management. Boards should make sure ESG data is correct, analyze environmental and safety risks, and incorporate ESG into the long-term strategy.

The results of strong governance companies tend to be high under projects undertaken and financial stability through avoiding compliance infractions and enhancing stakeholder confidence.

5.3 ESG Accounting and Financial Reporting

As part of reporting requirements, many companies now include ESG accounting construction sector data within their financial statements, particularly regarding environmental liabilities, contingent obligations, and asset-level risk assessments. Open accounting enhances investor confidence and better access of capital.

Conclusion: The Future of ESG Reporting in Construction.

Regulatory requirements, investor pressure and community scrutiny are shifting the construction business to a new era of sustainability transparency. Firms which develop good ESG reporting frameworks will enjoy better project approvals, better risk management and competitiveness. With the development of sustainability frameworks persisting, the capacity to gather high-quality data, actively manage risks, and show quantifiable improvements is what is going to make or break the success of the contractors in the years to come.